Louise Lawrence Transgender Archive (LLTA) has six scrapbooks, unique treasures of transgender history, a personal archive of photos and articles lovingly clipped from 1960s and 1970s newspapers, magazines and theater programs. When they were donated to LLTA, all we knew was that they had been compiled by a transvestite named Denise, who considered them her contribution to transgender history. But the scrapbooks were so idiosyncratic, so personalized that they demanded we discover the identity of Our Denise of the Scrapbooks.

Desperately Seeking Denise

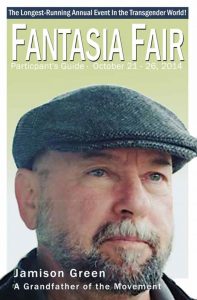

It All Started At Fantasia Fair

Just attending the 40th Annual Fair felt historic. “The Fair” is the longest running annual transgender event in the world. It’s given thousands the opportunity to live for one entire, glorious week in their gender of choice. And, unlike other getaways, the safe space isn’t limited to a hotel conference center and lobby. You can go sightseeing, to restaurants, bars, and galleries because The Fair is held in Provincetown, MA, as LGBT-friendly a town as can be found. It seemed as though the fates had put me there. Going wasn’t even my idea; I was invited to deliver the opening keynote by Dallas Denny, who was coordinating the speakers program.

Just attending the 40th Annual Fair felt historic. “The Fair” is the longest running annual transgender event in the world. It’s given thousands the opportunity to live for one entire, glorious week in their gender of choice. And, unlike other getaways, the safe space isn’t limited to a hotel conference center and lobby. You can go sightseeing, to restaurants, bars, and galleries because The Fair is held in Provincetown, MA, as LGBT-friendly a town as can be found. It seemed as though the fates had put me there. Going wasn’t even my idea; I was invited to deliver the opening keynote by Dallas Denny, who was coordinating the speakers program.

The Fair had been going for a few days when Taryn Gundling, who teaches anthropology and transgender studies at William Patterson University, introduced herself and asked if I would be willing to provide a good home for several old scrapbooks. I could feel my pulse quickening as I said, ”Yes,” so loudly that people across the room turned their heads.

(For Taryn’s account of receiving the scrapbooks from Denise read “An Unexpected Gift” elsewhere on this site.)

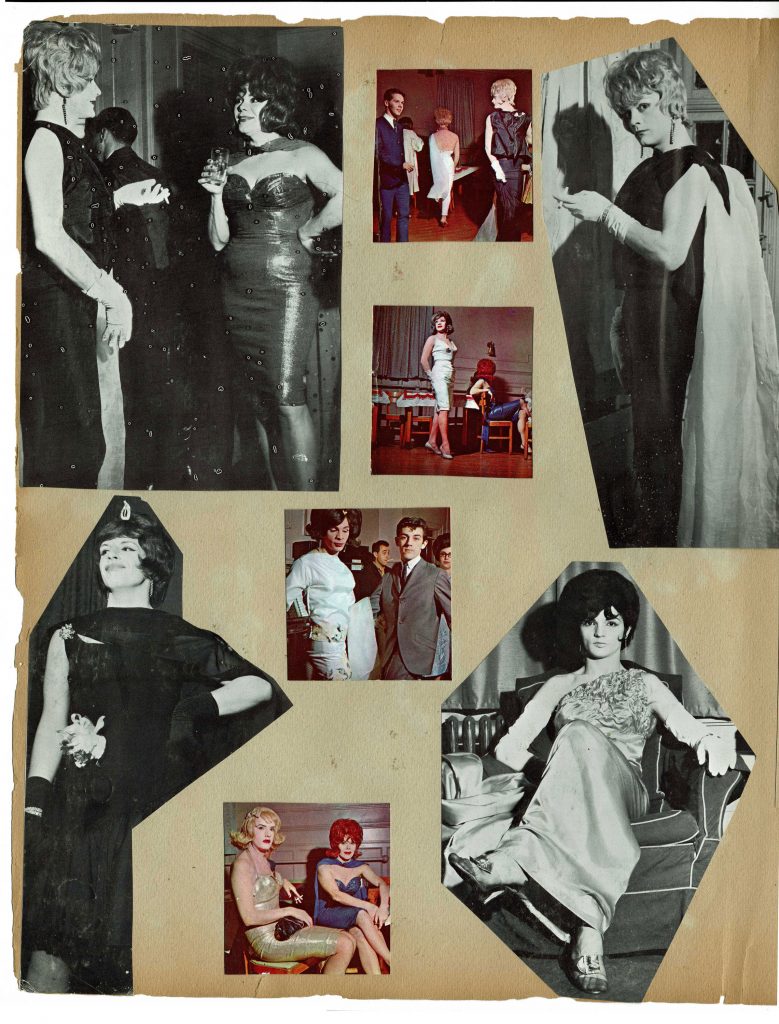

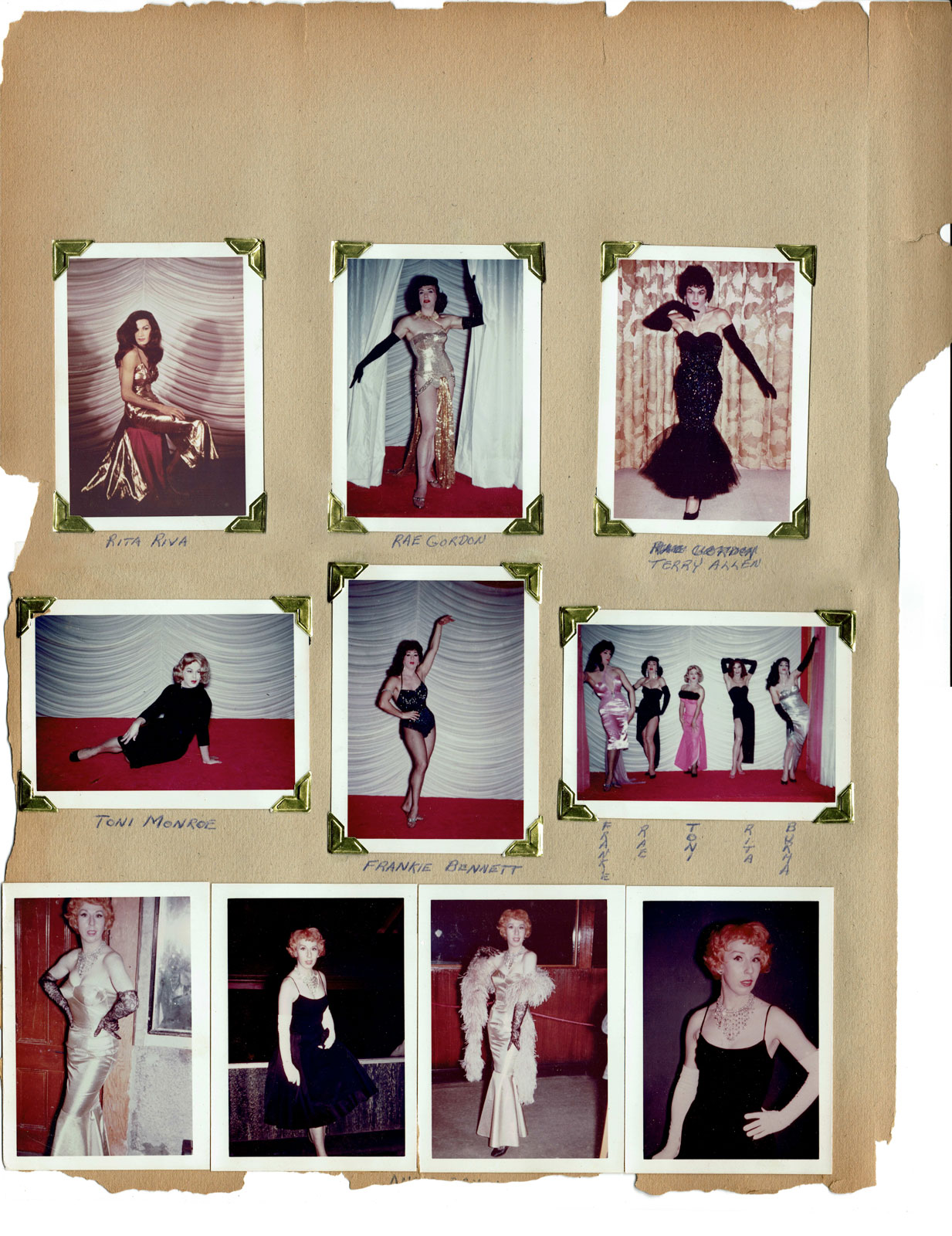

She brought the scrapbooks the next day. They’d been given to her at a support group meeting some years before. There were six of them in a plastic box about the size of a large picnic cooler. They contained thousands of trans-related clippings from newspapers, magazines, programs from female impersonator shows, supermarket tabloids, transgender contact magazines, and soft-core porn. They were a labor of love that must have taken hundreds of hours to compile. Scrapbooks, whether the contents is fields of flowers, favorite movie stars or female impersonators, are statements of identity. People save what’s important to them and scrapbooks mirror that interest as they preserve its place in the larger society.

She brought the scrapbooks the next day. They’d been given to her at a support group meeting some years before. There were six of them in a plastic box about the size of a large picnic cooler. They contained thousands of trans-related clippings from newspapers, magazines, programs from female impersonator shows, supermarket tabloids, transgender contact magazines, and soft-core porn. They were a labor of love that must have taken hundreds of hours to compile. Scrapbooks, whether the contents is fields of flowers, favorite movie stars or female impersonators, are statements of identity. People save what’s important to them and scrapbooks mirror that interest as they preserve its place in the larger society.

In an interview on the Smithsonian website Jessica Helfand, author of Scrapbooks: An American History (Yale University Press, 2008), says that, “When you feel an increased sense of vulnerability, what can you do to steel yourself against the inevitable tide of human suffering but to paste something in a book? It seems silly, but on the other hand, it’s quite logical” (Gambino). And by that logic, scrapbooks like Denise’s were inevitable in the 1960s and 1970s when transgender people were genuinely vulnerable.

By making scrapbooks, Denise was able to assert her gender identity, while maintaining the anonymity craved by many mid-century, middle-class transvestites. In the interview Helfand says, “Everybody made scrapbooks a hundred years ago, and people didn’t worry about getting it right. They just made things, and they were messy, incomplete and inconsistent. To me, the real therapeutic act is being who you are.” (Gambino)

Recognizing Old Friends

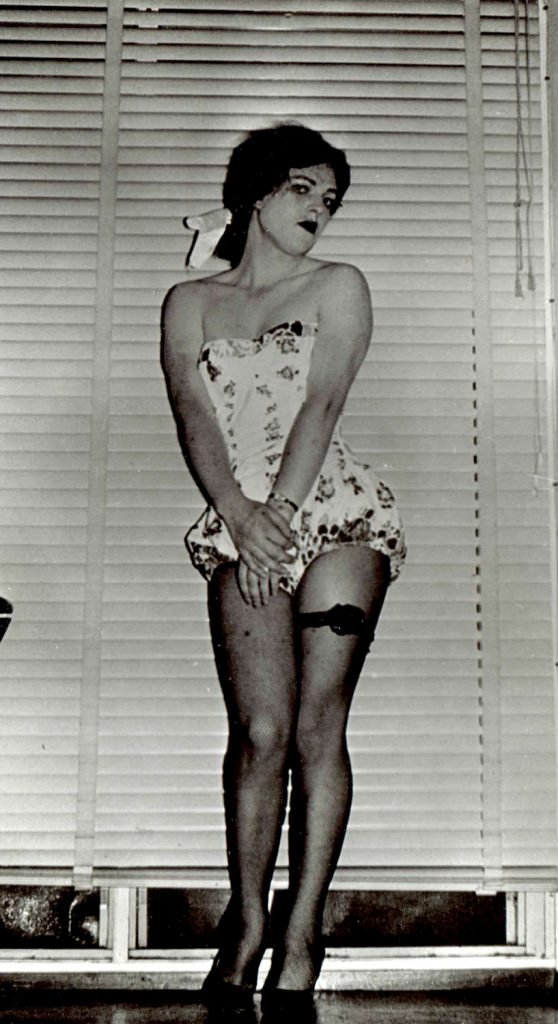

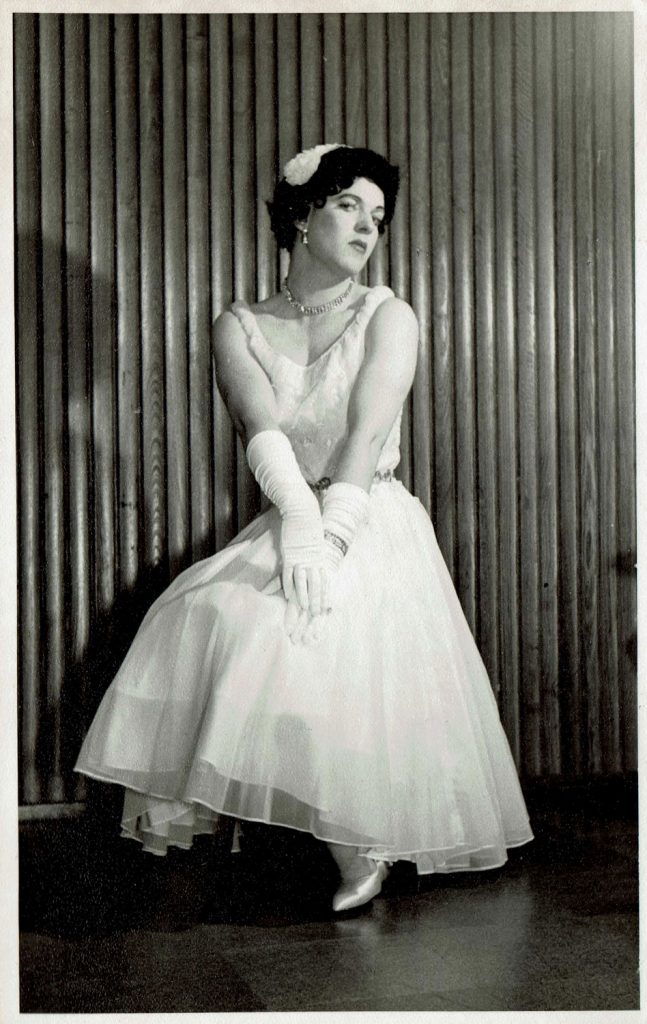

Five of Denise’s albums were all clippings, but one album contained over a dozen pages of photographs, snapshots, the kind mid-20th century cross-dressers sent to each other, and, what was more surprising, I recognized these people! I’d seen their photos before and some of them more than once.

There are three places I might have seen these people, even these photos.

The first was Casa Susanna, a book of photos from the personal archive of Susanna Valenti, who, with her wife Marie, owned a succession of Catskill Mountain resorts that served as safe spaces for transgender women to vacation in their gender of choice in the 1960s and 1970s. The first was Chevalier d’Eon Resort.

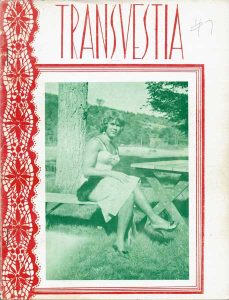

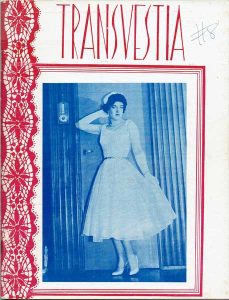

The second was Tranvestia. If I hadn’t seen the photos in Casa Susanna, it might have been in Virginia Prince’s Transvestia, the transgender community’s first national periodical, published from 1960 to 1986. Susanna and Virginia were movers and shakers in the mid-20th century American transgender community.

Virginia Prince from Denise’s scrapbooks, probably taken at Chevalier d’Eon Resort.

The third source was a more anonymous transvestite, Bobbie Thompson, whose personal archive is at the Louise Lawrence Transgender Archive. Photos from Denise’s scrapbooks appearing in Transvestia, as well as Bobbie’s and Susanna’s personal archives, meant that Denise traveled in the same social circles as Susanna, Virginia and Bobbie, social circles that are well-documented in Transvestia. This increased the likelihood that it was possible to learn more about Denise.

I thanked Taryn, then thanked her again. We promised to stay in touch. She said she’d try to track down our Denise. I took the scrapbooks to a shipping company and impressed upon them how rare and fragile they were, imploring them to pack Denise’s scrapbooks very carefully. Back home in the Bay Area, I began poking around the LLTA, looking for Denise.

The Search Begins

I started searching Transvestia for a Denise, any Denise. The results were encouraging. The cover girl for Transvestia, #7, January 1961, was named Denise. Her short autobiographical article began:

Click to view Transvestia #7 at the University of Victoria

I am 31 years of age, single but on the verge of taking the step. I am a college graduate and hold two degrees. My vital statistics are 38-28-38 (with the proper padding). I am 5’5 ½” and weigh about 145 lbs. I take a size 16 dress and I wish I could wear a smaller size (Denise 2).

There were lots of photos of Denise with the article. She was alone in all of them. Several were outdoor shots. One featured her sitting on a car, another at a picnic table. The rural setting made it possible these photos had been taken at Susanna’s Chevalier d’Eon Resort.

Although she gave her measurements and admitted that her bride-to-be had reservations about having a cross-dressing husband, Denise was rather cagey about other facts. Though, when describing how, to calm her bride-to-be’s fears, they sought counseling about Denise’s transvestism (TVism), she hinted about where she lived, Fortunately, I live in a large city and was able to see one of the foremost men in the sexology field and a man who knew a great deal about TVism (Denise 4). Virginia Prince, Transvestia’s editor, disclosed parenthetically that the learned sexologist who counseled the young couple was Dr. Harry Benjamin.

He (Dr. Benjamin) assured me that I was a perfectly normal male but that I had certain feminine characteristics as do most men. He also spoke to my fiancée and explained my practices. As of this writing the girl has accepted the idea that I will dress on occasion as a woman and she sees nothing harmful in the practice. (Denise 4)

Virginia’s identification of Dr. Harry Benjamin, put Denise in New York City, where Dr. Benjamin saw patients part of the year. This was confirmed by four photos in other issues of Transvestia. There were two photos of Denise in #5, September 1960 and two in #11, October 1961. The captions to all four was the same, “Denise – N.Y.” So, cover girl Denise lived in New York City, as did Susanna, when she wasn’t at the resort.

Susanna confirmed knowing Denise in “Susanna Says,” her long-running Transvestia column. In issue #8, March 1961, Susanna confesses that, while her New York apartment was full of “girl friends,” who could have used her help getting ready for the annual Halloween ball, she slipped out.

Under the pretext that one of us had to arrive early at the ball in order to hold on to the table we had reserved (which was true since late arrivals could find themselves without a table) I took advantage of one of the girls’ offer to drive me to the ball ahead of the others. She would drop me in front of Manhattan Center and drive right back home to get the rest of the crowd. (By the way, this was Denise (Cover Girl on #7) who did not dress for this affair.) (Valenti #8, 54)

So, Denise and Susanna definitely knew each other. There was one more mention of Denise in Susanna’s column, Transvestia #11, October 1961. More accurately, it’s a mention of Denise’s wife and, though it wasn’t conclusive, it bolstered the thesis that cover girl Denise and scrapbook Denise were the same person.

They tell me Denise is making a successful go in wedlock. Edith (how can that gal chatter!!!) is charmed and delighted with Denise’s spouse. She seems to be another one in the very small list of understanding wives. (Valenti #11 52)

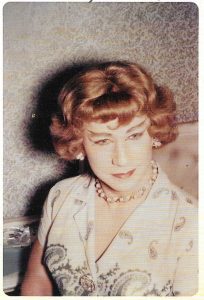

The Edith, who chatters in Susanna’s parenthetical, might be Edith Eden, another New Yorker who wrote the article “Edith Goes to Washington,” about her trip en femme to Washington D.C. in Transvestia #3. Photos of her are in the Casa Susanna book, Transvestia and Bobbie Thompson’s archive.

The Edith, who chatters in Susanna’s parenthetical, might be Edith Eden, another New Yorker who wrote the article “Edith Goes to Washington,” about her trip en femme to Washington D.C. in Transvestia #3. Photos of her are in the Casa Susanna book, Transvestia and Bobbie Thompson’s archive.

At this point we knew a bit about cover girl Denise; what she looked like, where she lived, that she knew Susanna and was recently, and happily married, but we still didn’t know if she was the Denise of our quest.

Searching In Earnest

The scrapbooks finally arrived. Five of the volumes were big, about 12” X 15” with hard cardboard covers. One cover featured a camp cartoon of a 1950s teenage girl busily scrapbooking. The interior pages were made of cheap, pulp paper, a little thicker than newsprint. They were yellowed, dried out and very fragile, making the scrapbooks seem even more rare and ethereal. You couldn’t touch a page without pieces flaking off the edges. The sixth scrapbook was smaller about 8.5” X 11.” Queer historian Gerard Koskovich respectfully labeled it, “the strangest example of transgender folk art I’ve ever seen.”

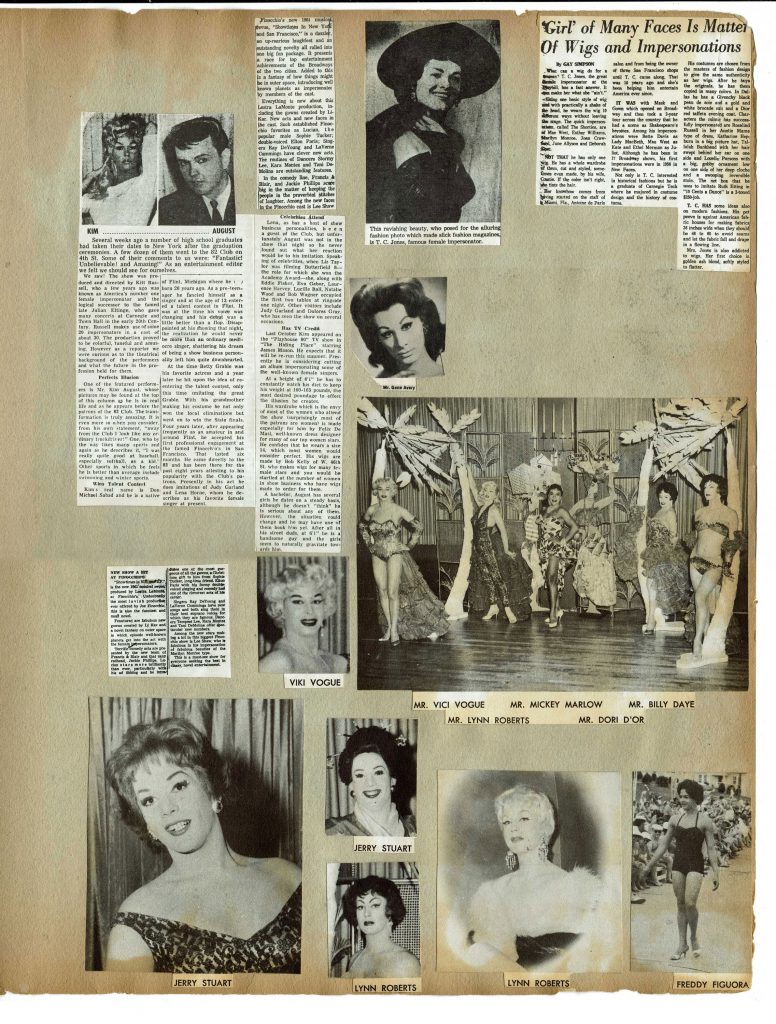

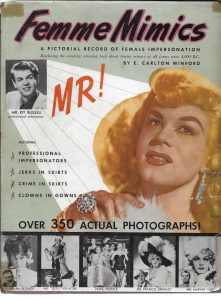

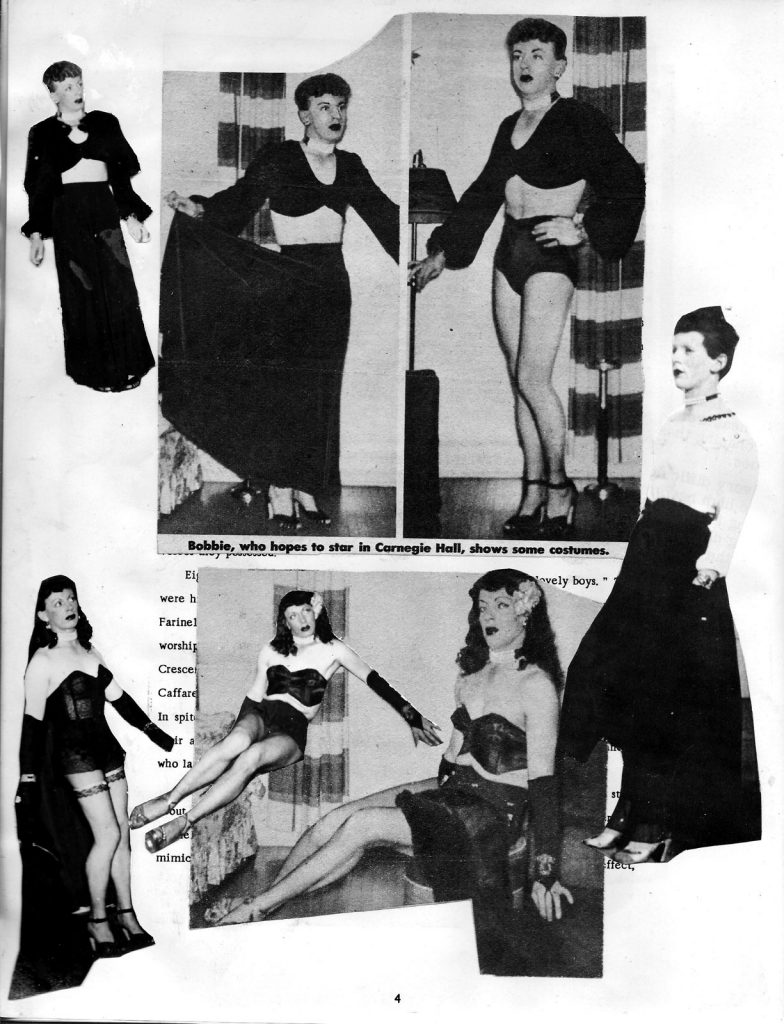

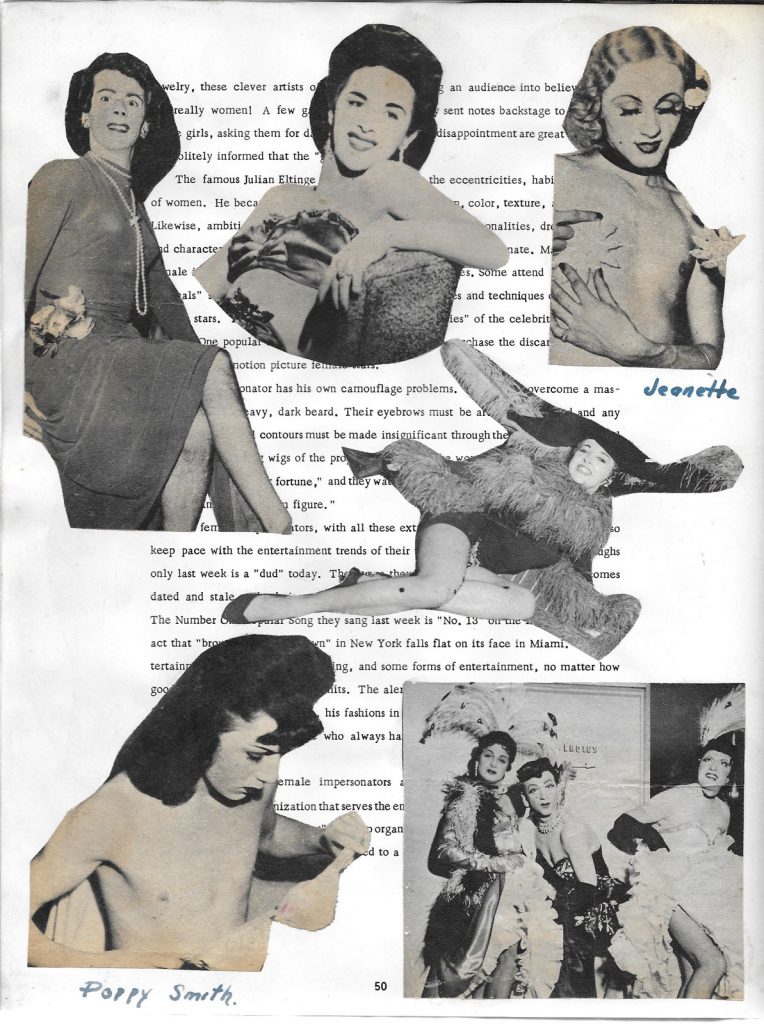

Denise had taken E. Carlton Winford’s oversized 1954 book, Femme Mimics: A Pictorial Record of Female Impersonation, and used it as a scrapbook. She pasted white paper over its pages, covering the original photos and text with both articles and photographs she clipped from mostly 1960s female impersonator magazines, like Female Mimics or Female Impersonator.

She scrapbooked about 50 pages this way, then she stopped using the blank sheets, and started pasting the clippings directly over the book’s text, so fragments of the original book are visible between Denise’s clippings, like a palimpsest, layer upon layer of text and photos. There’s even a clipping of vaudeville female impersonator Julian Eltinge taped over Winford’s text about Julian Eltinge. The only explanation I’ve been able to come up with is that Denise wanted a scrapbook that actually had the words Femme Mimics printed on the spine. The project was abandoned with about half of the pages unaltered. Perhaps Denise become discouraged when the binding split from the added bulk.

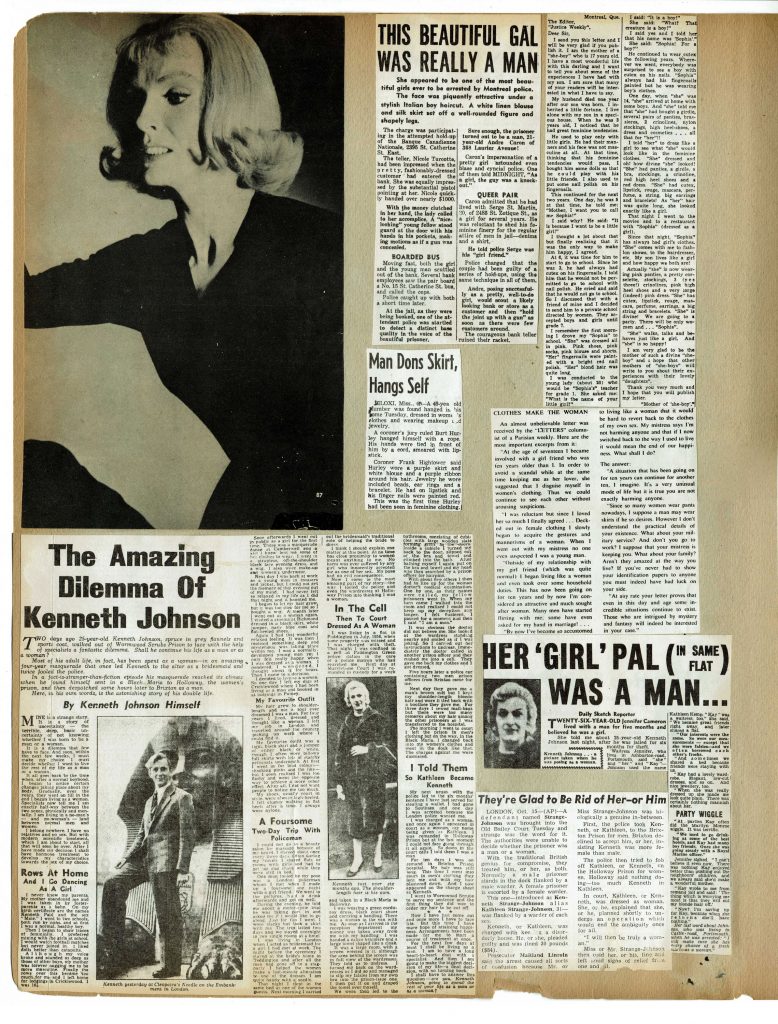

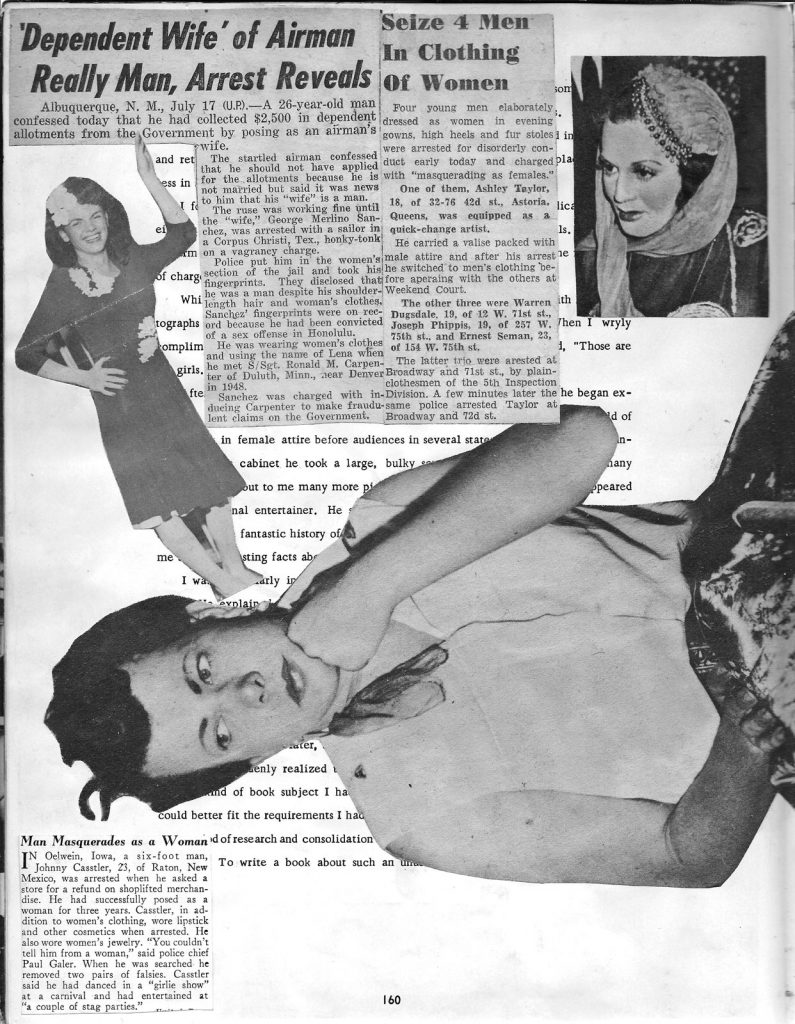

The photos and articles in Denise’s scrapbooks were about transsexuals, transvestites, female impersonators, cross-dressing criminals, female husbands, male wives, virtually anything transgender that was fit to print in the mainstream, tabloid, or soft-core press. Unfortunately, she didn’t provide any information about the source of the clippings, which is frustrating for a researcher. Five of the scrapbooks were all clippings that create a portrait of transgender in the mid-20th century, but the sixth scrapbook helped complete our portrait of Denise.

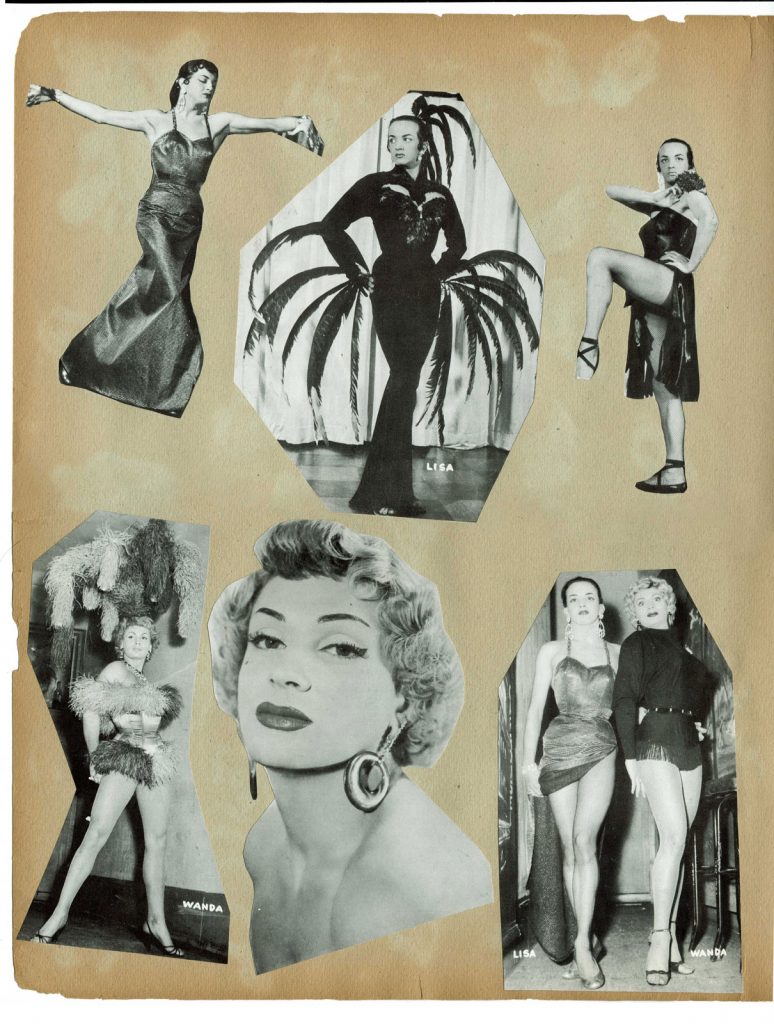

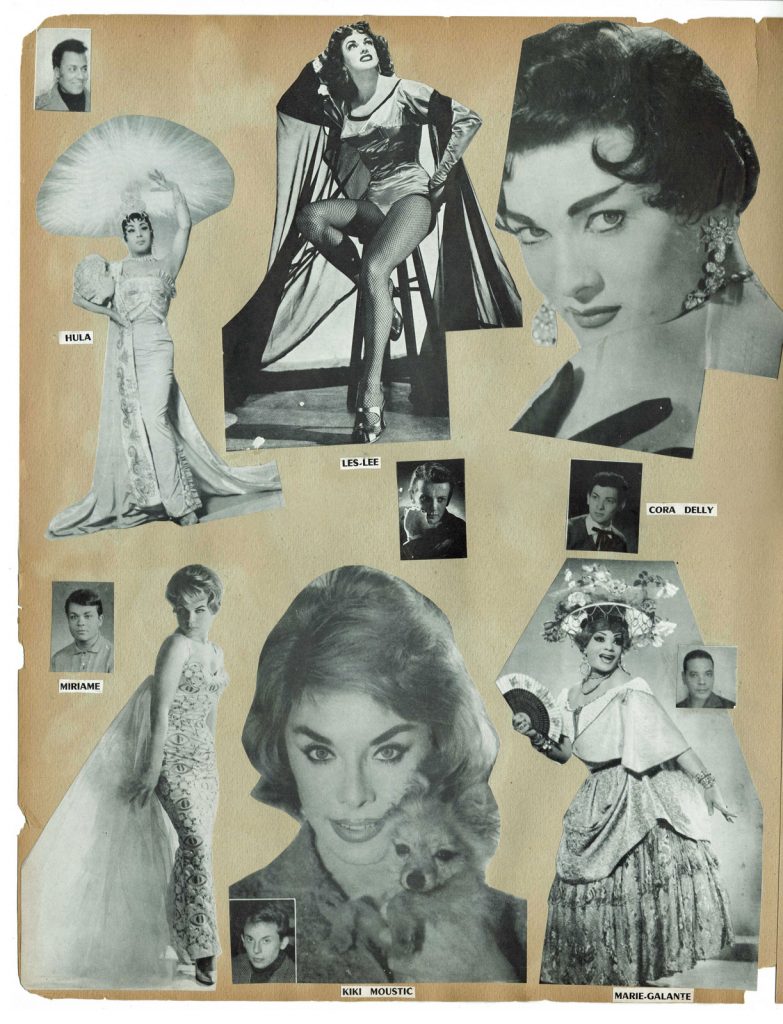

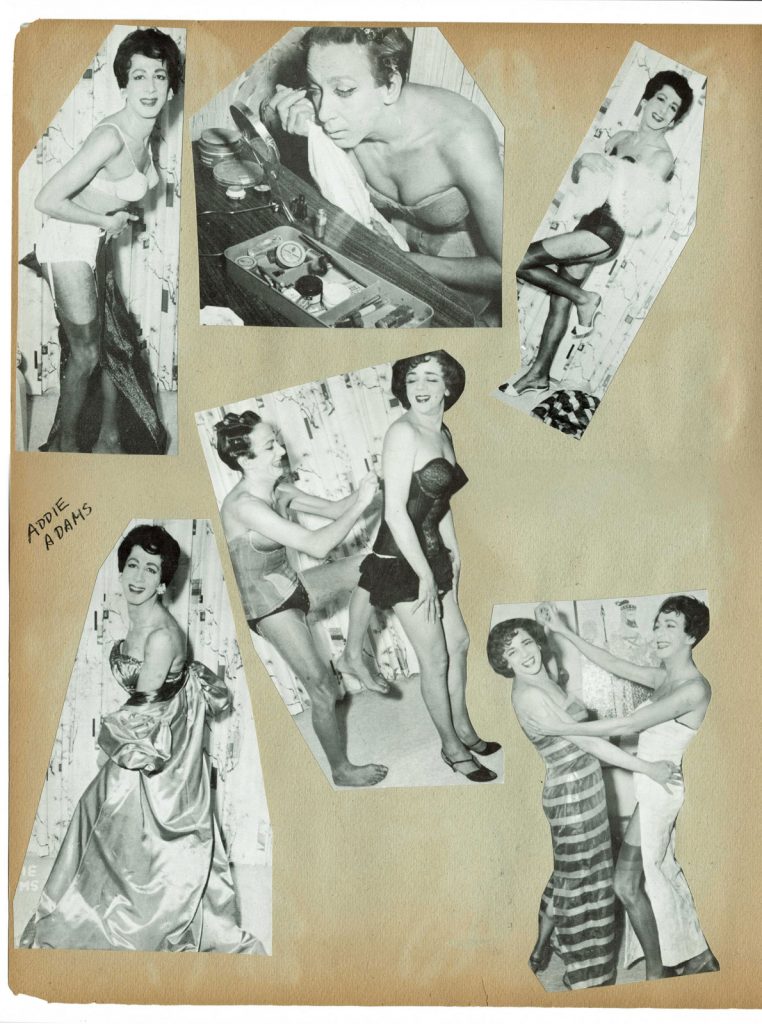

Below: Pages from the Female Mimics scrapbook.

A Peek at a Very Special Volume

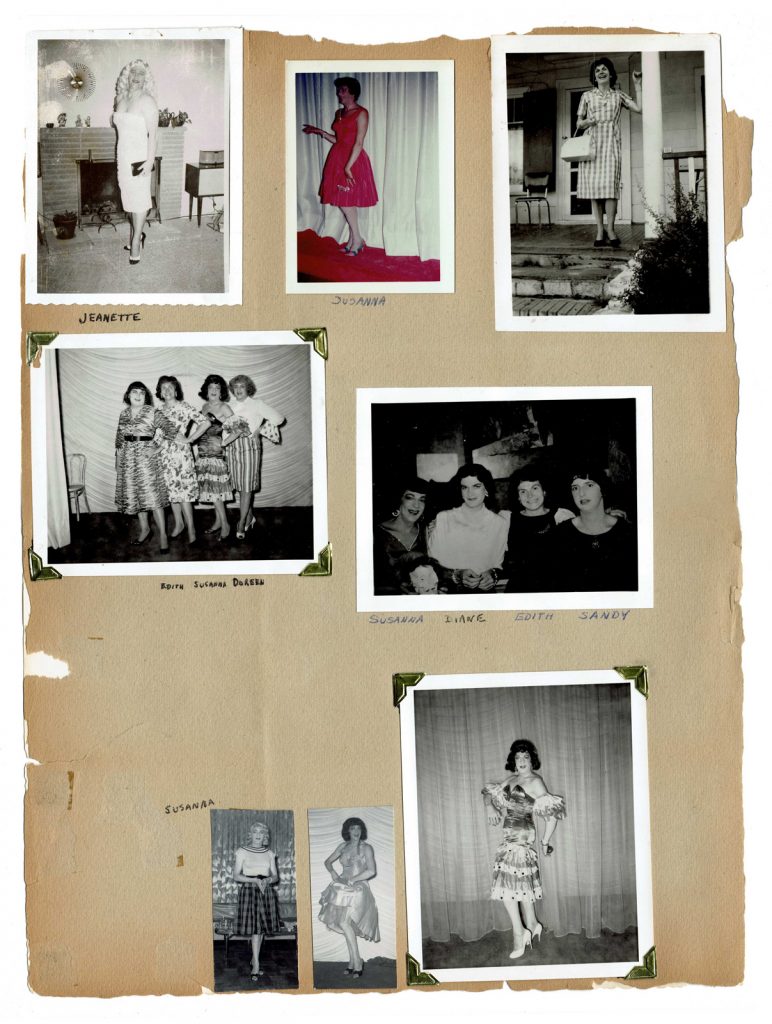

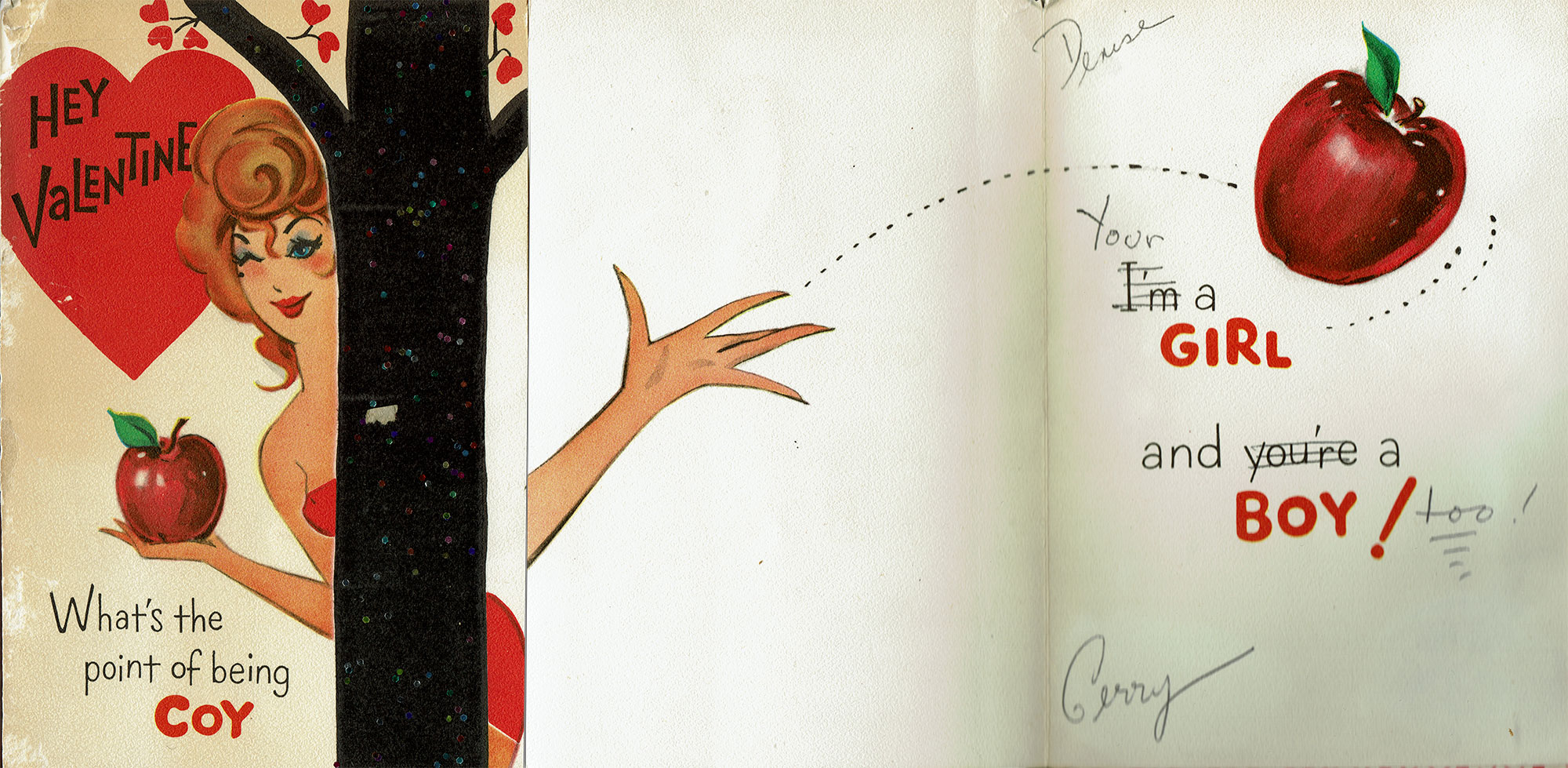

This sixth, more personal scrapbook divides into three sections. The first is the inside covers filled with greeting cards Denise pasted there: Valentine’s Day cards, birthday cards, even an anniversary card. The second section is the first 15 pages, an album of photographs of transgendered women. These two, the greeting cards and photos, tell us about Denise, unlike the remaining 60 pages, clippings of transgender interest like those in the other scrapbooks.

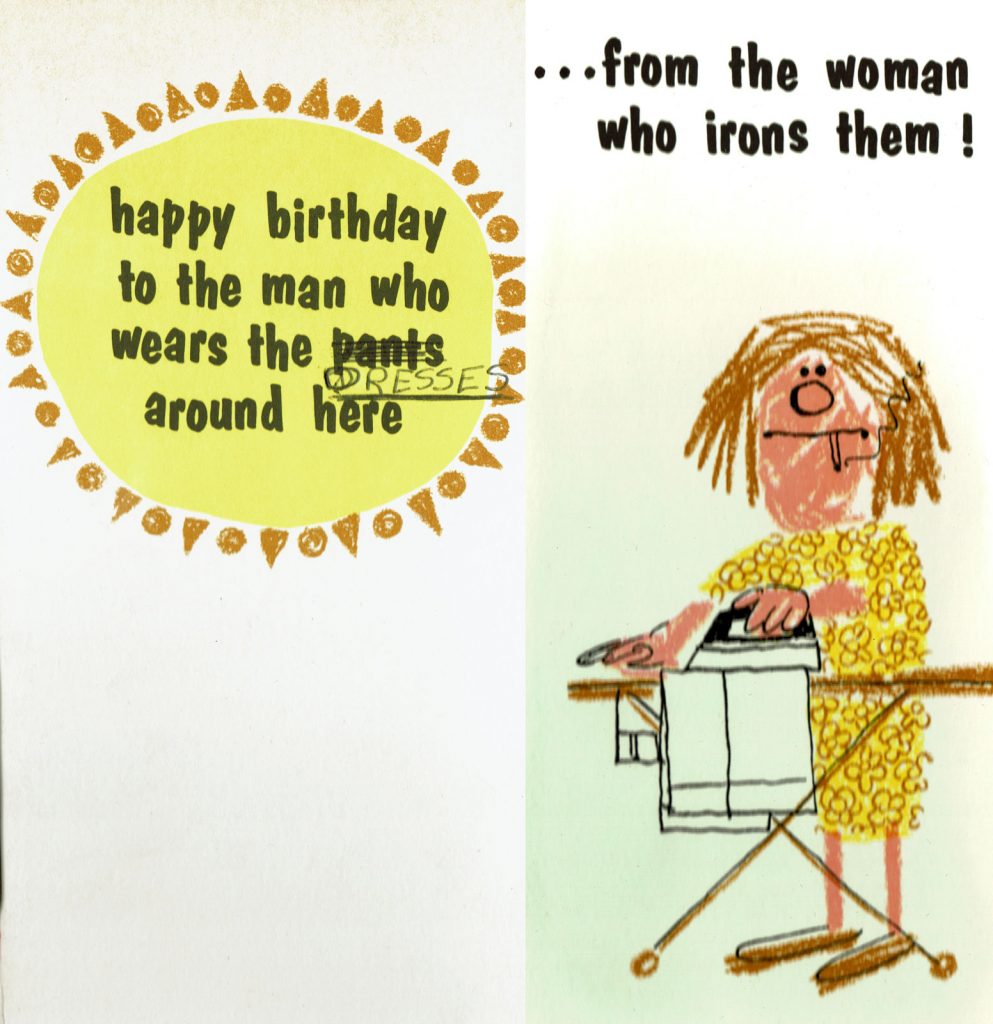

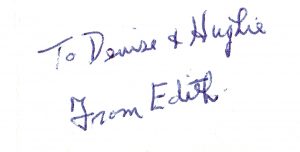

There are seven greeting cards in all: four from Gerry to Denise, one from Edith to Denise, and two from Denise to Gerry. The cards tells us that Denise’s wife is named Gerry and she seems just about as accepting of cross-dressing as a wife could be. It’s evident in the playful way the text was altered on several cards with words crossed-out and replaced by handwritten substitutes.

A good-natured example is the undated birthday card to the left.

A 1962 birthday card “from Edith” is addressed, “To Denise and Hughie,” which means that Denise’s male name was likely Hugh or Hugo. And I wondered if the sender was Edith Eden, who, according to Susanna’s column, had spoken so highly of Denise’s wife.

Finally, the date written on one of the cards suggested Denise’s birthday was November 29. In her 1961 Transvestia bio, Denise wrote she was 31, which means she was probably born on November 29, 1929 or 1930, depending on when she wrote the article. Taryn said that she received the scrapbooks, “sometime between 2009 and around 2011,” so Denise was about 80 when she gave the scrapbooks to Taryn.

The photo album provided information about Denise’s transgender social circle. She wrote the names of most people in ink below the photographs, though the edges had flaked off so badly on some pages that the bottom row of names is lost. There are several photos of Susanna Valenti, one of Virginia Prince, and photos of over 20 other transgender women. Susanna also appears in three group photos, two with Edith Eden. There are nineteen photos of Edith Eden spread over two pages: sixteen solo, the two with Susanna mentioned earlier, and one sitting on a man’s lap. Some had appeared in Transvestia; some in Casa Susanna. One is a photo Christmas card of Edith standing on stage at the Chevalier d’Eon Resort. The same card appears in Casa Susanna and, since Edith sent Denise a Christmas card, she probably sent Denise the 1962 birthday card, too.

There’s a full page of professional female impersonators, some shot on stage at Susanna’s Chevalier d’Eon Resort. Denise labeled one photo of two cross-dressers, “Lee Karen Halloween 1961,” but there’s no way of knowing if Denise was there, if she took these photos, or if they were given to her?

Above, the bottom row is four photos of Annie Saxon, but the paper has flaked off, so Denise’s handwritten caption is gone.

Surprisingly, there were no photos of Denise herself. Other personal archives, like Bobbie Thompson’s or professional female impersonator Harvey Lee’s, had dozens of photos of themselves. In Bobbie’s case, they compose the majority of the collection. It was obvious that Denise had removed some photos. In two cases the names of the people in the photos remained. One was of Jacqueline, the other Denise. These may have been photos Denise wasn’t ready to part with or, perhaps, she was being secretive and did not want photos of her cross-dressed in the hands of strangers, even transgender strangers. It is also possible that Denise kept photos of herself in another album. Both Bobbie and Harvey Lee had whole albums of themselves; Denise could have done the same.

The photos from Denise’s scrapbooks also appear in the three sources mentioned above: the Casa Susanna book, Virginia Prince’s Transvestia and Bobbie Thompson’s personal archive. Nine people in Denise’s scrapbook had either written articles for Transvestia or short autobiographies when they were Transvestia cover girls. It was clear that Denise, Bobbie Thompson, Susanna Valenti and Virginia Prince had a great deal in common. All were part of the same homogenous, post-World War II transgender network. All were white, middle class, college graduates, who were, had been, or were soon to be married to cis-gendered women. Denise, Bobbie and Virginia had advanced degrees. And, though Virginia was from Los Angeles, Denise, Bobbie and Susanna all lived in New York state.

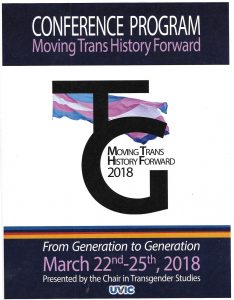

Though the greeting cards and snapshots provided more information about Our Denise of the Scrapbooks, the connection to cover girl Denise was still unproven. Cover girl Denise was an excellent candidate for Our Denise, but there just wasn’t any real proof. And that’s where the matter sat for the next few years until two things happened. The first was an exhibit at Moving Trans History Forward 2018; the second, hit me when I realized there was someone I’d overlooked.

Moving Trans History Forward at Moving Trans History Forward

Moving Trans History Forward is an academic/community conference presented by the University of Victoria’s Chair in Transgender Studies. On Saturday evening, right before dinner, there was an open house in the reading room of the Transgender Archive featuring an exhibit of highlights from their collection. There on the table was a page from Virginia Prince’s own photo album, a page of photos of Denise. I stopped short when I saw it and stared. I was transfixed. Other people looking at the exhibit had to walk around me.There were five photos on the page, including her cover girl shot from Transvestia #7. The other photos look familiar, too. I later saw that they had all appeared in Transvestia. I couldn’t believe I was seeing the original photographs. An information card next to the page said that all the exterior photos had been taken at Susanna’s Chevalier d’Éon resort. (I thought I’d recognized that picnic table.) This brought the two Denises closer together. Many of the photos in Denise’s scrapbook were taken at the Chevalier d’Éon resort and here was proof that cover girl Denise had been there. But, unfortunately, this new evidence, compelling as it was, was inconclusive. It did, however, inspire me to keep searching.

I was able to obtain a scan of the page from K. J. Rawson, director of the Digital Transgender Archive, which I forwarded to Taryn on April Fool’s Day 2018. I wasn’t sure Taryn had ever seen photos of Denise. She wrote back the same day:

OK, so I’m trying not to get too crazy here, but the individual in the lower left, white dress, pearls, seated in the field; that does in fact remind me of “our” Denise. I remember the asymmetry in the eyes. Amazing. Can I be 100% sure? No, but that image really struck me.

This was the best news I’d had in years and it got even better. Taryn wrote back a week later. She’d checked her personal journal and it turns out she’d met Denise at the Philadelphia Trans Wellness Conference in May 2009. “So, I already knew her before the Institute for Personal Growth support group in Highland Park, NJ,” where Denise gave her the scrapbooks. Then she added.

It’s funny, but I can see her face, and even hear her voice a little in my mind. Between you and me, I really do believe the pictures you sent are of our Denise…

The circumstantial evidence was piling up so high it seemed real proof had to be just around the corner, but actually it was halfway around the world.

The "Cover Girl from 'Down Under'"

Click to view Transvestia #8 at the University of Victoria

I took a hard look at Denise’s scrapbooks after the conference and then came the dawn. In Denise’s photo album were six photos of Joan. Joan was the “Cover Girl from ‘Down Under’” in Transvestia #8, March 1961, the issue after Denise.

Even though none of the photos of Joan in Denise’s album appear in Transvestia #8, I was sure it was the same Joan. The photos may have been different, but four of the outfits were the same as was one of the poses.

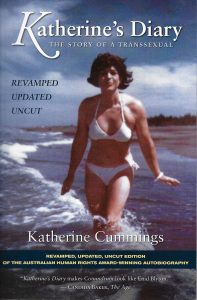

Nine years later in 1992 she published her autobiography, Katherine’s Diary: The Story of a Transsexual by Katherine Cummings. In her diary she devotes a whole chapter to the Chevalier d’Éon resort, calling it “The Resort With Two TVs in Every Room.” If Katherine knew Denise, she could put matters to rest.

Now I was desperately seeking Katherine Cummings. I contacted everyone I thought might have a lead. Transgender historian Susan Stryker sent me Katherine’s work email address. Susan thought it might still be good. It was and Katherine replied to my message on August 14, 2018.

Denise and Katherine’s friend Gail. This photo appears both in the Casa Susanna book and Denise’s scrapbook.

Yes, that is the Denise I knew from my time in North America when I was taking a post-grad course at the University of Toronto and later, I visited the States a few times from Australia, for conferences etc. I can’t recall her name (I am 83 and names are the first things to go) but I will either remember it two minutes after I press “Send” or I will check my old address books from the 1960s. I am a professional librarian so very few items are thrown away if they contain information, however useless it may seem. I attended the Casa a number of times although I only saw the first incarnation, which was called the Chevalier d’Eon Resort…I will get back to you after I verify Denise’s name. She and her wife were frequent visitors at the home of Gail, who was a dear friend of mine, and godfather of my American daughter. When I passed through the United States, I always tried to see Gail and, as I said Denise and her wife were usually invited for a meal, while I was there. My memory is suggesting that Denise’s first name was Hugh in her male persona.

That did it! Katherine suggesting Denise’s male name was Hugh matched Edith’s 1962 birthday card “To Denise and Hughie.” This, plus the circumstantial evidence, convinced me that cover girl Denise and Our Denise of the Scrapbooks were one and the same person! It had taken four years, three personal archives, two continents, and one firsthand account, but we finally knew the identity of our Denise.

That did it! Katherine suggesting Denise’s male name was Hugh matched Edith’s 1962 birthday card “To Denise and Hughie.” This, plus the circumstantial evidence, convinced me that cover girl Denise and Our Denise of the Scrapbooks were one and the same person! It had taken four years, three personal archives, two continents, and one firsthand account, but we finally knew the identity of our Denise.

Beside Denise’s identity, we learned something about the personal interactions between founding members of the contemporary transgender community. Much, if not most, of the writing in the early community is first-person accounts, people trying to define themselves and clarify their feelings. These articles from Transvestia #18, December 1962, are typical: “I Could Not Win Till I Lost,” “How It Was With Me,” “Twenty Six Days as a Woman,” and “The Wish to be a Girl and Wear Girl’s Clothing.” The fiction, too, is overwhelmingly in the first-person, “My Summer in Petticoats” and “I Played Tennis in a Pink Chemise.” Though there’s lots of confession, reflection and self-examination, much less is revealed about inter-personal relations. Seeking Denise and tracing the connections between people who knew her through the personal archives of others, not only uncovered the creator of the six scrapbooks, but also developed a deeper understanding of social connections within a broader transgender community; a greater appreciation of the humanity of these individuals which became visible through Denise’s scrapbooks.

SOURCES

Denise, “Cover Girl for January – Miss Denise,” Transvestia, Vol. 2, #7, January 1961, p. 2 – 7.

Gambino, Megan, “The Cherished Tradition of Scrapbooking: Author Jessica Helfand investigates the history of scrapbooks and how they mirror American history,” smithsonianmag.com, May 13, 2009. Downloaded July 11, 2020.

Hurst, Michel and Robert Swope, eds. Casa Susanna, powerHouse Books, NY, 2005.

Thompson, Bobbie, “Bobbie Goes Public – A True Story,” Transvestia, Vol. II, No. 8, December 1962, p. 59-63.

Thompson, Bobbie, “Bobbie Goes Private,” Transvestia, Vol. III, No. 22, August 1963, p. 2-11.

Valenti, Susanna, “Susanna Says,” Transvestia, Vol. II, No. 8, March 1961, p. 53-57.

Valenti, Susanna, “Susanna Says,” Transvestia, Vol. II, No. 11, October 1961, p. 49-54.

Winford , E. Carlton, Femme Mimics: A Pictorial Record of Female Impersonation, Winford Company, Dallas, Texas, 1954.